"THE LION AZURE"

Battlefield Communications In General

By Dean Wayland

<

1. Introduction

Summoning allies, lighting the beacon!

Return of the King, Lord of the Rings Part 3.

Click image to view clip.

|

War is the art of attempting to master chaos, while causing your enemy to lose before you do. To this end, good communications is an essential asset, especially so, if your life really does depend upon it. Fortunately few of us these days find ourselves at the sharp end of a real war, however, wargaming in all it's varrieties, especially simulated live action combat games such as airsoft, lazer tag, paintball, historical re-enactment and fantasy live role playing wargames requires a clear understanding of the arts of communication. So, whether you are actually serving in the real-world, or just enjoying the "fun" parts of war without the pain and tears, then this article has been written just for you.

|

Central to the art of war is good communications, for without it military power is paralysed and essentially useless. Therefore one of the key principle objectives of warfare is the dual goal of protecting and maintaining one's own lines of communications, while at the same time attempting to intercept, subvert or destroy those of the enemy's. To do this effectively you must first master the arts of communication itself, employing a variety of means, some high-tech, others quite primitive. Remember that exclusive reliance upon high-tech solutions alone can be fatal, for their expense, reliability and safety may limit or preclude or impede their deployment. Always ensure that you and yours have a back-up or three. And in all cases when using any method of communication in a combat situation it is vital to remain calm and to think before you act. Therefore keep it simple and concise. Panic and over excitement lead to haste and complexity, which will only serve to confuse both you and your allies, and in turn end up aiding your enemies.

2. Uniforms

|

The most simplistic message you will ever need to send is a statement of allegiance. Today this is done by the wearing of distinctive military uniform, with insignia of various sorts, permanently or semi-permanently attached. In many paintball, airsoft and large scale LRP engagements simple coloured armbands, headbands or sashes are used to identify one side from another. The same practise was done during NATO military exercises, where the good guys wore blue armbands and the bad guys wore orange. This is the origin of the saying "blue on blue" for an incident of friendly fire, when troops from the same side accidentally engaged one another.

|

|

|---|

Above right: Even something as utilitarian as camouflage clothing can function as a group identifier on the modern battlefield. U.S. Army Rangers equipped with MultiCam® uniforms (2007). Click image to enlarge.

NB:

In 2010 all British land forces were issued with a variant of MultiCam®, called MTP (Multi Terrain Pattern), the intent being to render its wearers distinctively British while still wearing one of the world's latest generation of transitional camouflage patterns.

|

Members of medieval armies, carried distinctive shields or wore badges, "livery" jackets or "surcoats", either indicating personal identification or some form of group allegiance. See the Lion Azure at the top of this page as an example of a badge being worn upon a yellow ground. It is the heraldic emblem of a fictional unit from an alternative 15th century, click the image to go to the old (2005) Lion Azure page to learn more.

In Japan, crests known as MON were painted on to the front and rarely the back of body armours and helmets of lower class warriors for the same purpose. Those of rank sometimes wore a small flag called a SASHIMONO attached to the back of their body armour, again providing either group or personal identification. Sometimes these SASHIMONO carried written messages of intent, like naming an intended victim and what the SAMURAI was going to do to them if they found their enemy on the field of battle.

During a night battle in Italy in the early sixteenth century, one army removed their white under-shirts and wore them over their armour, so they could tell friend from foe in the confusion of the darkness. On the other hand, during the Battle of the Bulge in the winter of 1944, some English speaking German special forces troops wearing US Army Military Police uniforms infiltrated allied lines and wrought havoc by tampering with road signs, redirecting or slowing traffic, and interfering with other communications systems.

Right: A SAMURAI in full armour having a SASHIMONO affixed to his backplate by an attendant. Click image to enlarge.

|

|

|---|

|

Left A medieval personal banner bearer (me) holding position close behind the then unit commander, Paul Thompson. Note the red livery jackets with white stars (mullets), denoting that they are retainers of John De Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford's household forces. The Earl of Oxford's household of The White Company, leading the attack during the 500th anniversary re-enactment of the Battle of Stoke (1487) in 1987. Click to enlarge.

What ever you choose to use, apart from it being appropriate to the kind of game being played, historical, modern, fantasy etc., the identifying mark, device or clothing must be distinctive to be effective. For as many accounts from the past prove, the absence of, or the wearing of similar identifying devices can cause disasters as at the Battle of Barnet in 1471.

|

Here elements from each side had very similar badges on their livery jackets, and when returning to the fight, having just driven an opposing unit from the field the Earl of Oxford's troops were mistaken for the enemy.

3. Verbal/Vocal

This is the use of whispered or shouted words and phrases or non-verbal cries to send prearranged signals or complex messages over relatively short distances in any conditions. For the majority of human beings the act of talking is the most basic of communications skills, but on the battlefield like so many other things in life its not always quite that simple. In battle you will find yourself fulfilling both the role of the giver and taker of orders, but when performing the role of a unit commander, whether it be as a Corporal in charge of a four person "Special Forces" style team, or as a General responsible for a medieval army of 1,500 souls, you have two methods available to you. Say it yourself, or delegate, via a subordinate or a messenger.

|

Left: R. Lee "The Gunny" Ermey, click image to see him in his infamous and outstanding role as the US Marine Corps Drill Instructor Hartman in the movie Full Metal Jacket (Run time 5:58). Ermey in fact served 14 months in Viet Nam as part of an 11 year career in the US Marine Corps, before becoming an actor and TV presenter, see his

Wiki entry.

When having to do this kind of communications at short range, DON'T get carried away screaming and shouting, you will waste your breath, energy and possibly wreck your throat and consequentially lose your voice, which will render you less than useless to your compatriots. Only do this when absolutely necessary, for example when winding your people up ready for action, getting them motivated, initiating a taunting chant and the like. Whenever possible delegate the task if you can to a subordinate, unless this will undermine your authority as the unit commander.

|

|---|

In all other cases leave the general and continual business of jeering and taunting of the bad guys to the grunts, while you get on with making sure that your side is the one that wins.

|

Right: But then again, the one exception is when it falls to you to give the eve of battle speech, which only you as the commander can give. This can if required be delivered with a quiet dignity. For example click the image of Colonel Tim Collins at right and watch Kenneth Branagh portray him giving his famous eve of battle speech to the troops of the 1st Battalion, Royal Irish Regiment of the British Army, as the prelude to the invaision of Iraq in 2003, taken from the BBC production 10 Days to War. (Runtime 3:30)

Simple non-verbal shouts, can serve well to initiate actions, such as an attack, distraction or retreat, but more complex orders need to be issued with care. Firstly, pause, and THINK, what do you need to say? Having worked that out, you next need to get the attention of your audience. Merely giving the order and expecting it to be acted upon, when dealing with essentially undisciplined and excitable civilians doing this for fun in a highly distracting environment, is living in "cloud cuckoo land".

|

LTC Tim Collins

|

Take a deep breath and shout out an appropriate phrase something like "LISTEN UP PEOPLE", repeat IT if necessary until you've got their attention. This usually has the desired result, especially once people have got used to this vocal "bing-bong" noise meaning shut up and pay attention. Alternatively, when dealing with a large and vocal body of troops, this "listen up" signal, can be given by audio-visual aids, such as air horns, trumpets, drums, flags or as I did in the role of army commander at the massive LRP events called

"The Gathering"

during 1992-95, raise your commanders baton (mine was a distinctive Japanese war fan). Wait until you have silence, which with the help of subordinates, eventually you will have. Then speak, deliberately, clearly and with pauses. Keep your announcement short and simple, repeat it if necessary and get an acknowledgement from your audience, confirming that everyone has both heard and understood the message. A phrase like "EVERYBODY GOT THAT?", followed up with "ANY QUESTIONS?", usually beds things down nicely. Then send them on their merry way with something like "OKAY PEOPLE, LET'S DO IT!" Obviously the precise language used must be appropriate to the era and culture being played.

At the other extreme, when trying to talk covertly at night by whispering, do not allow your chest to resonate as the resulting low frequencies can carry the "noise" a long way, while at the same time probably rendering it difficult to be understood at even close range. Use a hushed "head voice" whisper instead, it is both clearer and limited in range due to its higher frequency. Remember to speak deliberately, slowly, and clearly, ensuring that you look towards the intended audience and don't move your head about while speaking, as this will cause the whispered message to become unclear, thus wasting precious time in unnecessary repetitions.

These points are especially important when wearing a respirator or paintball mask, as such devices muffle regular speech and hide the mouth preventing the additional aid of "seeing" what you are saying. Do not be afraid to whisper loudly, you may think it will betray or deafen you, but your team members stand a better chance of hearing your words, especially in foul weather.

The other method for sending a verbal signal is via a messenger, or a runner as they are sometimes called. They have an unlimited range, particularly when compared to the size of a typical playing area, but are relatively slow, unreliable and of limited security as they can be captured and their messages extracted through "torture" and or bribery.

To be effective messengers should be able to prove both their own identity and that of the person for whom the message is intended by the use of special code words/phrases (

Authentication Codes) and not just simply by their dress or even documents. Better still the messenger should be known to both sender and receiver if possible. Allied groups should arrange this well ahead of time, and messengers should be well versed in the kind of military heraldry in use, such as flags, unit insignia etc.

4. Improvised/Manual Signals

This is the use of natural or artificial devices to send very simple prearranged audio/visual signals over very short distances, such as breaking twigs, throwing objects like stones into the air or into water, or at other objects to make them move or ring.

In modern style covert operations the tapping of a weapon's body or magazine to attract attention in the "listen up" role is commonly used as a prelude to a hand signal.

A modern replica of the D-Day "Cricket" clicker

|

During the D-Day landings in June 1944, members of the 101st Airborne Division of the US Army, who parachuted behind enemy lines needed a method for identifying one another in the early morning darkness during the post drop regroup phase. The troops were issued with a children's toy, called a "Cricket" or "Clicker", which when operated made a sound much like the insect. Unfortunately, this was the same as the sound of the German Army's standard Mauser Kar-98 rifle's bolt action mechanism being worked slowly, which did lead to some problems! Replicas of this toy are still being made today.

Obviously these techniques can be employed to attract or distract attention as required, but things can become overly complicated if you try to ascribe any special meaning to such signals.

|

|---|

On the other hand, stones, branches etc. can also be used as improvised markers, either to flag up problems, like mine fields, active booby traps and the like, or to give an indication of the presence of a given unit in an area. Items such as common playing cards have been used in this role. A well known marker is a pair of crossed sticks upon disturbed earth, meaning that the location was used as a latrine.

Great caution and care is recommended in the placement and recognition of these "signs", as they can occur naturally, or be moved by wind, animals or unscrupulous bad guys!

5. Recorded Media

|

This is the sending of simple or highly complex messages, written or recorded in plain or encoded format, on paper, wax tablet, slate, magnetic tape, CD, DVD disk, SD card or thumb drive etc., by means of a messenger or via a drop point. As mentioned above messengers or runners, are slow, unreliable and they can be intercepted and their cargo captured. Drop points or "dead letterboxes" as they are known in intelligence circles, are only of value while they remain secure. Such features can not only be used by an enemy to plant disinformation, but also to act as the focus for an ambush, or act as the starting point of a tracking mission.

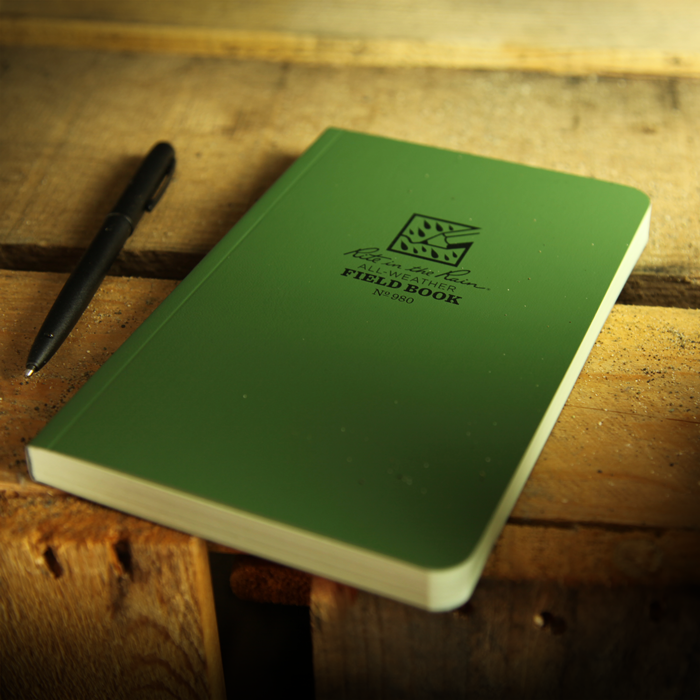

Left: A 'Rite In The Rain' Field Book. A notebook with waterproof paper that can even be used under water, with the correct pen and ink that is. Click the image to see my article on

Hand Writing For The Battlefield.

|

|---|

6. Military Hand Signals

These are the various systems of visual hand gestures used to send set signals or complex messages over very short ranges in reasonable light, using either sign language as employed by the deaf, semaphore or Wig-Wag or the like (see below), or the much simpler military hand signals systems employed for infantry or vehicular actions, and surface to air communications. See

HERE

for the infantry hand and arm signals article.

7. Flags & Insignia

|

This is the use of either flags of allegiance, personal "banners", unit "standards" or personal insignia to distinguish friend from foe and to gesture very simple prearranged signals over moderate distances in good light, particularly during historical style engagements. Even today the white flag is recognised as the international signal communicating the desire to surrender, or as a flag of truce used to prevent bloodshed during negotiations between otherwise hostile forces. The simple raising of one's colours to signify the capture or conquest of an objective is still seen on the modern battlefield. Alternatively they can be used as a means of abuse as when US Marines covered the statue of Saddam Hussein prior to pulling it down.

|

|

|---|

Above: The toppling of Saddam Hussein's statue while covered With the US flag.

Battle for Baghdad, Iraq, 2003. Click image for video (Run time 1:07).

|

|

Left:Notice just how well the blue lion on a yellow ground stands out on "The Lion Azure" standard which is being carried by myself at the 2002 Renewal LRP battle event. Renewal is

Curious Pastimes' rival event to

The Lorien Trust's The Gathering, following its split at the end of 1995. For the '01 season I decided that it was time for me to reprise my role as a humble banner bearer, which was way more relaxing! The unit's heraldry and title were taken from my partner's novel ASH: A Secret History. Click image to go to the old Lion Azure page.

Starting with the use of flags in the pre-modern era, we first meet the "banner" which is a personal heraldic device, moderate in size and very distinctive in nature. They can be either in the form of a traditional flag or a three dimensional object.

|

|---|

|

They are used to mark the identity and location of a unit's commander, so that subordinates and messengers can look across the field and find them. The banner bearer sticks to their "boss" like a limpet mine, going with them wherever they do. This role should only be given to people who are genuinely reliable, one who requires constant chivvying by their commander should be replaced.

Duplicate banners with "battle doubles" is an expensive tactic only worth doing for senior or wealthy commanders in very large scale events. When it is used, all these seemingly identical banners should be equipped with a unique mark or device, like an attached miniature pennon style flag, one of which identifies the real commanders position for that specific engagement or time slot. The unit as a whole does not follow this kind of flag unless directly ordered to, as in "FOLLOW ME!"

| |

Right: Battle lines of the 1993

Gathering

live rrole play 1,500 a side free form battle. Note the enormous red and yellow triple Lion "great standard" in the centre, carried by Neil Ashman, which I used to control the entire army's movement.

The "Standard" is the larger style of flag that is used to identify individual units or an entire army, and normally marks their centre. The unit as a whole moves with its standard, thus a commander need only give an order to the standard bearer to advance 10 paces, to in effect order the entire unit to move forward 15 metres.

|

|

|

FYI - A Useful Tip: a Pace is in reality two steps, being for all practical purposes 1.5m. The original Roman mile which was around 1,500m long, gets its name from the Latin for '1,000', being the number of paces in a mile. Armies in the past, and even units in the field today sometimes have to resort to pace counting to navigate. Indeed the US Rangers still issue a set of beads for that very purpose, especially useful in triple canopy, that is, really dense jungle, where it is often impossible to get a GPS signal. Try it yourself, it is far easier to count each time your right foot strikes, the ground, compared to attempting to count every foot fall. Click image to enlarge.

|

|

|---|

The cry or bugle call "LOOK TO THE STANDARD" was used to get people to pay attention to the movement of the unit's flag. Likewise "RALLY" is used to get the unit to regroup around the formations centre when its personnel have become too spread out, disorganised and vulnerable.

During the 1987 Summerfest, the very first of the large public mass battle LRP events in the UK, I commanded a night battle wherein several factors contributed to our success. I kept the 200 strong 'army' together as a single square, with a spotter at each corner, a flag at our heart, and a very reflective two-handed sword given to the tallest fellow in the army, to act as a pointer. Using the spotters to advise the location of the numerous smaller enemy units, I directed our sword bearer to point in the appropriate direction, and following an order to "LOOK TO THE STANDARD!", on the count of one, two, three, the army as a whole pounced...

Sadly "officially" we lost for reasons of plot, but all who fought that night knew otherwise, so I was pretty happy with that.

|

Left: US Army rank insignia of a Sergeant Major, as used by the UNMC. Click the image to go the Rank & Insignia pages.

A commander would often carry a baton, war fan or similar device to clearly mark them out as the person in charge. Today this task is performed by rank insignia, which is normally small and subdued in nature to prevent attracting the interest of enemy snipers. However some commanders prefered to stand out.

|

|

|---|

Above right: US General George S. Patton, 3rd US Army (1944~45), was famed for wearing a pair of pistols with white ivory grips and a brightly pollished set of stars on his helmet.

All these devices could be used to direct troops in the field, or give pre-arranged signals. For example again in the 1993 Gathering battle, I used the dipping of our army's standard three times as a signal to a large enemy unit to change sides and execute our pre-arranged plan, and yes it worked very well, much to the surprise of the enemy army. As previously mentioned I also used my "baton" (war fan) as a signal requesting silence, invaluable when you are trying to brief or direct 1,500 people in a field in the middle of England.

All this made controlling a medieval or later period army much, much easier, and this is why such flags and devices were considered so important and why their bearers held such high status. If the flags were captured, unit cohesion vannished, swiftly followed by any thoughts of victory. National flags, or a Regiment's "colours" were not merely pretty props with bragging rights, or trophies to be captured, they were instead serious working tools of the art of war. Use them correctly and they can turn the tide of battle, even today.

Today flag like devices and equipment markings are just as important upon the modern battlefield for the successful control of forces. Vehicle and aircraft markings, often only visible in the infra-red are commonly used to sort friend from foe. Brightly coloured (orange) and reflective (silver) ground marking panels, can be found identifying safe zones like hospitals and the like, or resupply, landing or drop zones, as well as rescue pick-up points, or even minefields, and are typically included in modern survival kits

Still, national or international flags are invariably mounted upon vehicle antennas, or painted or magnetically mounted upon their sides, as much as a symbol of pride as allegiance.

8. Signal Flags

Sending actual detailed messages over distance using visual means dates back to ancient times. For example,

the Roman army used a system for sending messages from fixed point to fixed point, using a set of wooden flags mounted on a rack. The precise visual pattern displayed represented a letter of the Roman

alphabet, and in concert with a code book, enabled a wide range of messages to be rapidly sent. They also had a method for doing this at night using burning torches, but more of that later.

The first true signal flags were instituted by the Royal Navy in 1653, a system notably improved by Lord Admiral Howe in 1790, and Captain Sir Home Popham in 1799. In 1817 Captain Frederick Marryat published his A Code of Signals for the Merchant Service, the first civilian system, and In 1854 it was renamed The Universal Code of Signals for the Mercantile Marine of All Nations due to its widespread adoption. Then in 1857 the British Board of Trade published the Commercial Code of Signals, which evolved in to the current

International Code of Signals

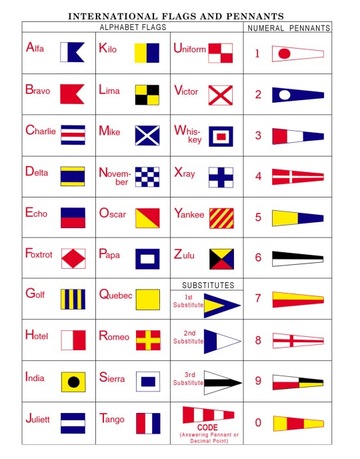

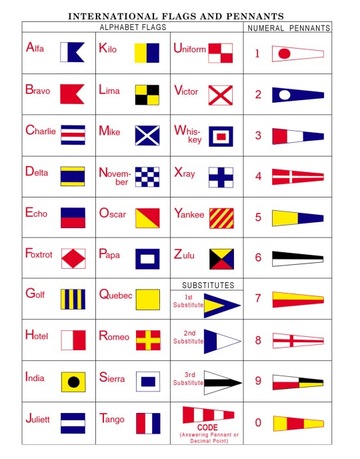

or ICS, now universally used by the merchant marine and the majority of navies, including those of NATO.

When raised together these groups of signal flags are called a hoist, and comprise a mix of numbers and or letters, which are assigned a special meaning defined in a code book. Thus enabling the transmmission of many thousands of set messages. Of course you can if desired spell out a message in plain text, however this would be far too slow for most practical purposes. The importance of a hoist is inversely proportional to the number of flags used. Single or double character messages are assigned the most important meanings, while those with three are of a medical nature, and longer ones are concerned with the day to day running of a vessel and personal messaging.

Even today, hoists are still regarded as the best communications options for certain circumstances, as their impact is normally restricted to the area immediately around the signalling vessel, and do not effect others that may not need to know. For example the signal advising that the vessel has a diver in the water, or it is currently taking on fuel.

|

|

Left: The square red and yellow OSCAR (O) Naval version of the ICS flag, which is traditionally used for semaphore when at sea. Click to enlarge.

Right: The square Naval version of the PAPA (P) flag of the ICS, aka the Blue Peter, which is used for semaphore on land. Click image to enlarge.

Below right: A chart showing the civilian edition of the International Code of Signals (ICS). Click the image of the chart to enlarge.

|

|

|---|

|

The ICS is used mainly by professional sailors as it requires regular practise to produce an adequate level of expertise. For example the Blue Peter or PAPA (P) flag pictured above right, can also be used to send the message: "All persons should report on board as the vessel is about to proceed to sea", or alternatively when at sea fishing vessels use it as a warning to advise that: "My nets have come fast upon an obstruction."

Note that the large OSCAR and PAPA flags and the ones in the chart at right are slightly different. This is because even today naval signal flags although identical in pattern are square in shape, whereas merchant marine flags are rectangular. Also navies use entirely different square numeric flags when talking to one another, fortunately there is now a NATO standard. And yes they also use the ICS pennants too, plus several special naval flags. See this

US Navy web page for an idea.

On land, pre-dating the use of the well known modern semaphore flag system (below) the US Army in 1860 adopted a single flag signalling system popularly entitled Wig-Wag, devised by an army doctor named Albert James Myer in 1856. This used a single flag in one of three positions to send a code not unlike Morse. Indeed at more or less the same time two British officers; Vice Admiral Philip Colomb and Sir Francis Bolton independently created a similar method but actually using Morse's code. Wig-Wag was used widely by both sides during the American Civil War (1861 ~ 1865). See this demonstration by an ACW re-enactor on YouTube:

|

|

|---|

Post war there were disputes as to which method was best, Wig-Wag or the British system, and so the US Army ended up teaching both between 1886 and 1912, when the British system was adopted fully. The method of sending Morse by flag continued in service until just before WWII, when it was officially replaced by Semaphore, but it lingered on until the end of the Korean War (1950 ~ 1953), simply because for Morse users it was just so easy to use and did not require them to learn an entirely different system, despite having a slower transmmission speed.

Left to right: the Wig-Wag flag for a dark background, the Wig-Wag flag for a bright background, the British Morse flag for a dark background, and the British Morse flag for a bright background. NB: each flag came in two or three sizes for use at different ranges. A small flag would be about 38x38cm (15"x15"), and the largest could be 1.8x1.8m (72"x72").

|

Left: A US Navy sailor sends the semaphore letter "U" during a replenishment at sea operation. Note the red and yellow OSCAR (O) flags, which are traditionally used when at sea for semaphore. Click to enlarge.

Flag Semaphore is the only other flag signalling method still in use today, other than the ICS. It is a simplified version of the original system devised in France by Claude Chappe and his brothers in 1792 that used towers and large mechanical arms and called a Semaphore Line. Over 500 of these towers were built by Napoleon as a prelude to his military campaigns, click the BBC logo at left to see a short video about one that has been rebuilt. (Run time 2:29)

Flag Semaphore became increasingly popular around the end of the 19th century, and is today simply referred to as just Semaphore.

|

|---|

It is the system of using both arms with or without flags, to send relatively complex messages over moderate distances in good light. Each arm can be placed in one of 8 positions, at least 45° apart, their combination determining the character being sent. A pair of flags are normally used to extend the arm and make it easier to read the signal. At sea these flags are traditionally the square red and yellow OSCAR (O) flag of the Naval edition of the ICS, whereas wehn used on shore the square PAPA (P) or Blue Peter flag is used. It ultimately won out over using flags to represent the Morse Code, as it was capable of much higher transmission speeds and was very easy to learn, especially by those not trained to use Morse Code.

|

The system is still taught and used by Special Forces to send short ranged messages using just the arms. Ideal for challenges and authentication codes at distance in good light. Incidentally, as Special Forces tend also to be taught Morse Code as well as Semaphore, they can also use the British Morse flag signalling system too! Click the YouTube link to see how to send a rescue request in semaphore:

|

|

|---|

Despite the advent of radio, microwave and laser communication systems, these techniques are still taught and used in combat by armoured formations, naval units, maritime air forces and special forces, as an emergency back-up. See the

Battlefield Communications Semaphore, and

Battlefield Communications Morse Code articles on how this system is used for the issuing and responding to challenges in CONTACT.

9. Musical Instruments & Devices

|

Left:A bugle, the common military signaling instrument of the 19th century

This is the use of wind or percussion instruments, such as whistles, horns, trumpets, drums, bells and gongs, to send prearranged signals over moderate distances by day or by night. These have the advantage of not needing to be seen to be effective.

Anyone who has seen a western, wherein the cavalry come to the rescue with their bugle blasting out the commander's orders is familiar with the basic principle.

|

|---|

On one rare occasion back in 1995, I made use of a trumpeter to provide three very simple signals to around 1,500 souls, "look to the standard", "charge" and "run like hell", the latter coming in very handy indeed - ah, the fortunes of war...

Although for us, the use of the ordinary personal whistle is restricted to out-of-character use for genuine emergencies only, during the Vietnam war the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Viet Cong (VC), made extensive and successfull use of sports whistles to issue command and control orders. Watch and listen to the movie Platoon, you'll get the idea. And let us not forget the blood chilling impact of the use of the whistle in World War I, for the signal to go over the top.

Of course if you have the skill, you do not actually need a whistle, a pair of fingers and some puff will do for an attention grabber.

|

Left: the 'All Weather' Storm Whistle®, the world's loudest whistle, which actually works under water too. The best emergency whistle on the market. Quite large as whistles go at circa 83x45x23mm (3.25" x 1.75" x 7/8"), but then its designed to be used while wearing gloves, when wet, and in the bitterest of cold. Comes in orange, yellow and black, and is used by the military and anyone involved in maritime service, rescue operations, or just for hiking in the mountains of doom...

Click the image at left to see a short demonstration by the inventor Dr Howard Wright, while up to his neck in water. (Run time 1:37)

Right:Click the image to see a video comparing the Storm Whistle with what the makers state on their website is the world's second loudest whistle, the Windstorm (shown), made by the same company as a slightly more compact edition, at 70x38x23mm (2.75" x 1.5" x 7/8"). Again presented by the inventor. (Run time 1:11)

|

|

|---|

|

Left: Japanese whistling signal arrow. Tokyo National Museum.

The SAMURAI warriors of old Japan, used whistling signal arrows called 鏑矢 KABURA YA (かぶらや) literally "humming bulb arrow". This was achieved by the affixing of a lightweight bulbous turnip-shaped wooden or horn arrowhead pierced to act as a whistle while in flight. Sometimes, like the one illustrated at left, they were surmounted by a lethal point as well. The type shown called a KARIMATA or "Wild Goose", was a forked blade which was often shot at horses. The two together would have made a very effective anti-cavalry weapon I suspect.

Here are two short videos; the first is a Japanese archer loosing a single KABURA YA (whistling arrow), and the second is a group of western archers letting loose an entire salvo of whistling arrows. Run times are 0:30 and 0:46 respectively.

Finally the incredible impact upon morale of the presence of inspiring music on the battlefield should never be underestimated, just ask the Ottoman Turks, the Japanese and the Scots. Here then are three very different examples of music for war from around the world, play them loud the way they were meant to be heard and you will get the idea:

Firstly we have Turkey, formally the Ottoman Empire, who have the oldest continuous tradition of actual military bands leading the troops on the battlefield. Listen to their most famous march, believed to be 800 years old Ceddin Deden. (Run time 2:25)

Next the SAMURAI of old Japan were summoned to battle by the beating of the "great-drum" or TAIKO, here are three being played by the famous

TAIKO group Koto. (Run time 8:24)

Then again there's the Scots, not for nothing were the pipes and drums regarded as weapons of war, try this piece from the 2013 Edinburgh Tattoo. (Run time 7:03)

|

A whistling arrow

Volley of whistling arrows

Ceddin Deden

TAIKO

Pipes & Drums

|

|---|

10. Fires, Flares, Smoke, Lamps & Burning Torches

This is the use of incendiaries like bonfires, candle or oil lanterns, burning torches, and pyrotechnics (firework like devices) to produce light, sound, or smoke, to send prearranged signals over short to moderate distances by day or by night. Their effectiveness depends upon the device employed, such as coloured smoke grenades, thunder flashes, or hand held or aerial flares, and even tracer fire. Until the advent of the pager and the mobile phone, it used to be that off shore lifeboat crews were summoned to action by the firing of a series of aerial maroons, producing a report sufficiently loud that it would be heard all over the town.

Simple signal fires or beacons, like those used to alert the English to the arrival of the Spanish Armada in 1588, are famous, as is the fictional beacon of Minas Tirith which is an example many of you will have seen on the big or little screen. see the image at the top of this article from the movie Return of the King, the third of the Lord of the Rings trilagy. Here a great bonfire or "beacon" is lit to summon allies of the city of Minas Tirith to the war in the land of Gondor. Click the image to see the clip from the movie (Run time 2:56).

These signal fires can range from the plain bonfires used across the world, through to the Japanese fire baskets that were fixed to a swing arm mounted upon a tower, so that at the pull of a rope the signal could be raised 10 to 20 metres into the air.

Across the world during the middle ages fire arrows and rockets were often employed for sending pre-arranged signals by day as well as night. In daylight the smoke trail was normally sufficient to serve the purpose.

The ultimate form of this kind of signal fire being that devised by the Romans. It used a burning signal torch combined with a standard size water vessel with a bung at its base. The operator kept their torch hidden behind a barrier, than raised it and awaited a similar signal from the other post, once seen, it would be hidden again to order the bungs at each post to be removed. The torch being raised again once the level of the water had fallen to the desired height, to signal that the bung should be inserted and a set message read off the float and a table.

With the development of lense grinding in the middle ages, lanterns could be used to send simple signals, although it was not until the 1840's and the creation of the Morse Code and similar techniques, that more complex signals could be sent. (See section "12:Cable" below.)

|

Modern armies make extensive use of audio-visual pyrotechnics, such as coloured smoke for signalling. Indeed there are specialist grenades made for this purpose coming in a tremendous range of colours. For example the M18 violet smoke grenade illustrated at left and right. They are used for example as a means of confirming identity; a unit radios in a request to cross friendly battlelines, the reply is an order to "pop smoke", and if it is the correct colour the unit will survive the move across the line, at which point a verbal challenge will be issued.

|

|

|---|

⚠ FIRE, FIRE, FIRE! ⚠

|

Be aware that whenever burning compounds were, or are used, great care and sensible management of these potentially risky tools has had always to be taken, to avoid unwanted death, destruction or injury. For civilian re-enactors or live action wargamers, this need is doubly so. There will be days or nights when the weather and/or driness of undergrowth will dictate that pyrotechnics are simply unsafe, and must not be used.

|

|

|---|

|

|---|

11. Heliographs (Mirrors)

This is the use of metal mirrors made of copper, bronze, brass, silver, iron or steel, or ones made of glass or plastic, employed to reflect strong sunlight in limited directions, sending simple signals or complex messages using systems like the

Morse Code over short to long distances. (See section "12: Cable" below.)

|

⚠ WARNING ⚠ Note that glass coated mirrors should for reasons of safety never be used in re-enactment or live role-playing where there is any risk of it ending up on the battlefield. In a non-combat zone they're fine.

|

As long ago as the Egyptian empire, these techniques were in common usage. Even today such devices are common in modern survival kits.

Before the advent of radio, the longest ranged pier to pier signal was set by the heliograph. The British Army operating in India achieved an effective range of over 160km (100 miles). At the same time Royal Navy vessels also used these systems, for one thing, they did not need a power supply and they were light and easy to maintain. Only problem was that they did not work at night.

An excellent tool, if you can find one, is the British Army's 1945 pattern issue polished stainless steel shaving mirror, which comes in a green cotton case, and measures about 127x76mm (5" x 3"). It is pollished on both faces, and provided with two holes; the first near the top to enable it to be hung up for shaving, and the second dead centre, so it can double up as a heliograph. Not only can you signal by day, but if you are in trouble and the search parties are out looking for you, a heliograph can be used to reflect their lights by night. It can also be used for looking around corners!

The technique to use it is simple; view the target via the centre hole, position yourself in relation to the sun so that in your reflection you can see a spot of light upon your own face. Now tilt the mirror so that the bright spot of light vannishes in to the centre hole. Each time this happens the person at the other end will see a flash of light - simple.

Alternatively, here are two modern examples of the heliograph.

Click image to enlarge, or visit

The Bushcraft Store and have a look.

|

Left: The Star Flash Signalling Mirror. The 21st century survival heliograph, made by Ultimate Survival Technology, 76x51mm (2" x 3"), unbreakable and even floats .

Right: The TOPS Signalling Mirror. This is a hard chrome double sided metal mirror, that is the same size as a standard military dog tag 51x29mm (2" x 1.125"), and comes complete with a rubber dog tag silencer. This is the smallest heliograph I have ever seen, designed so you can wear it with your dog tags.

|

Click image to enlarge, or visit

The Bushcraft Store and have a look at this one too.

|

12. Electrical & Chemical Light Signalling Devices

This is the use of electric torches, lamps, strobes, and chemical light sticks for sending simple or complex signals over all ranges by day and by night.

The common military flashlight fitted with either coloured bulbs or filters, and a shroud to reduce the brightness and to direct the light, have been a key signalling tool since the First World War for air, ground and sea services. Using

Morse Code, messages can be sent over quite long distances. (See section "12: Cable" below) In

CONTACT such flashlights are used to issue and respond to challenges at night.

|

Strobe lights or flashing LEDs can be employed as either as rescue tools, equipment or personal beacons, either to attract attention or to avoid it. An example of this latter case is the use of infra-red strobes to mark individual troops on the battlefield as part of an Identification Friend or Foe (IFF) system. In

CONTACT red flashing lights are used at night by casualties to atract medics, and to help them to avoid being trodden on in the dark. Unfortunately it can also attract the enemy's interest too.

|

|

|---|

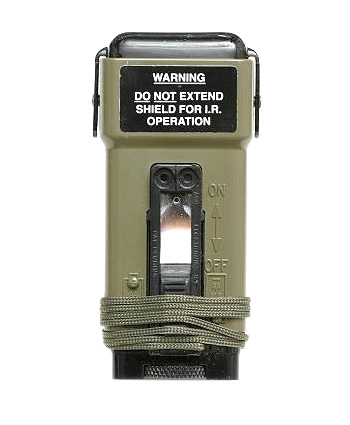

Above left: the Energizer ACR MS2000 Military Strobe. Click image to vistit UK-Tactical.

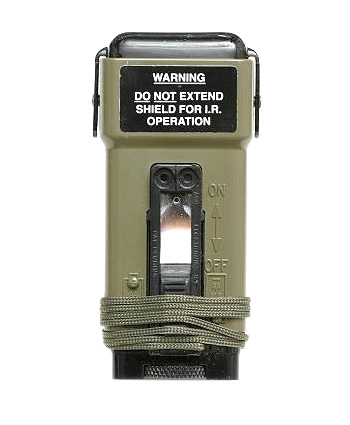

Above right: the Streamlite Sidewinder torch, with movable head. It has four sets of LEDs; in white, red, blue and infra-red. It can be set to constant, or to flashing mode.

|

Left: 'The' genuine NATO issue US Army right angle flashlight, which has remained in service for signalling, ever since its introduction during the Viet Nam war. The Fulton MX991/U comes fitted with a standard bulb, a sliding on/off switch and a flasher button for Morse Code, which has protective guards to prevent accidental activation. A screw on/off base stores a defuser lense, an amber, a red, a blue, a green and a white filter, plus a spare bulb. The front section unscrews to allow filters to be added or removed (I always leave the red over white filter in place to dim the output and avoid unwanted reflections), and it runs off 2 D cells. Available in olive drab, black and an indeterminate dark camouflage pattern from

Cadet Direct.

NB: there is now an LED bulb replacement kit, that includes a battery cradle for 2 AA cells, making the flashlight, much, much lighter to carry, while maintaining its effectiveness as a signal light. The reason for the lower power is so the LED doesn't melt the torch! The LED conversion kit is not yet available here in the UK, but I have made enquiries. The kit is available directly from the US maker

Fulton. Click image to enlarge.

|

|---|

Weapon mounted torches (tactical lights), with a thumb operated button on a cable, can also be used in this role, but tend to be too bright, and usually lack coloured filters as standard. But in an emergency they will serve.

Chemical light sticks can be used as route, equipment or hazzard markers, or even for traffic control of vehicles or aircraft, as they can be visible over quite long distances by night. They come in quite a variety of sizes, and brightness/duration. In

CONTACT we use the brightest (5 minute runtime) as a kind of weapon to incapacitate one of the types of zombie like enemies within the campaign. The device having to be attached to the enemy in a location from which the hostile cannot remove it - makes for an entertaining sport.

|

NB:

All these visual techniques are strictly line of sight, heavy rain, snow, fog smoke and obstacles such as trees and building seriously reduce their effectiveness. Security can be enhanced by the use of shrouds to make a light source more uni-directional, and coloured filters or even pierced metal covers can also be used to either reduce output and/or provide additional information, such as sender identity. Operators wishing to send more complex messages will need to master the Morse Code, however for sending alpha-numerical challenge and passwords, you only need to memorise the numbers and a handful of the simplest letters, see my article

Battlefield Communications Morse Code for more information.

BTW Remember earlier I mentioned the development of lense grinding during the late middle ages? Well this was swiftly followed in about 1600, by a Dutch inventor creating the worlds first telescope, which had obvious scientific and for this discussion, military potential. Today, with weapon mounted optics, aerial drones, and cameras capable of seeing in the dark, as well as at long ranges, any visual signalling technique has had its effective range significantly enhanced, a factor often over-looked by some re-enactors and gamers.

|

⚠ LASERS ⚠

|

Note that lasers, whether for communication or target marking/illumination purposes, should NOT be considered as eye safe for use in these kinds of games, but ONLY for genuine life or death military/police applications.

|

|

|---|

|

|---|

|

|---|

13. Cable

This is the use of wires or cables linked to equipment at potentially global ranges, capable of sending complex messages by Morse Code (telegraphy/telex/teletype), speech (telephony) or audio/visual (television) or data transfer via computer modem over wire networks and the internet.

|

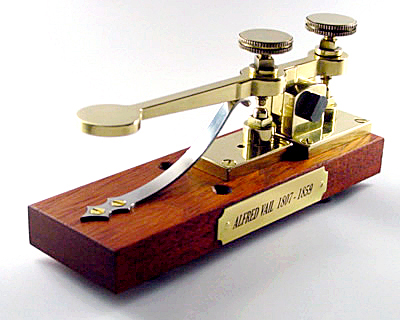

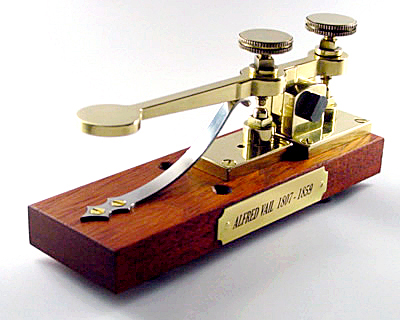

Samuel F. B. Morse devised his famous code during the early 1840's for use with the new telegraphy (landline) technology, as well as lamps, heliographs and signal flags (Wig-Wag/British Morse Flag Signalling), but it would eventually also be employed with automatic systems such as telex or teletype, and even hand and arm signals. Today it is still taught and used by Special Forces and radio amateurs for use with radio. His original code later became known as American Morse and was extensively used by both sides throughout the American Civel War (1861~1865). However it was replaced almost immediately after the war, by the International version, which was an 1851 modification by the Europeans to solve some technical issues concerned with its use with underwater cables. This is the version that we know today as

the Morse Code. And like the bugle, if you have watched enough westerns, you will have seen someone sometime sending a telegram along the wires that ran alongside the railroad tracks, and no doubt an Indian cutting it!

|

|---|

|

Above: A beautiful reproduction of the brass telegraphy key used by Samuel F. B. Morse for his first demonstration in 1844. Click image to visit the manufacturer's website.

Right: The J38 WWII era US military type telegraphy key, which are still in use with radio amateurs for the sending of Morse Code via radio. Although today fully electronic keys are more popular as they are easier and less stressful to use, and enable more accurate and much faster rates of transmission.

Below: The US TA312 Field Telephone, click the image to see the webpage about these sets.

|

|

|---|

|

By the time of the Boer War 1899~1902, armies were turning to the field telephone, and Morse was then only used by signallers using radio or lamps. The telex or teleprinter carried on in use right on up until the 1990's as it was a very reliable system. These systems were eventually superceeded by the internet.

Devised during the 1980's, and only gaining public recognition and usage during the 1990's, the internet today is the core of global communications. However, the internet itself is only really of use to games with fixed assets, or ones where computers, tablets etc. can access the net via WiFi. The military of course can use satelite communications to access the network.

|

However amateur radio operators can employ VOIP (Voice Over Internet Protocol), and other services to create networks linking their own in-country radio nets with the internet, and anyone anywhere can join in and contribute. So using Skype for example, someone who can not get to a game, but would still like to be involved can provide intelligence support to people on the ground from anywhere on the planet at no real cost.

In real life engagements such systems suffered badly from the effects of artillery fire, as in the trenches of World War 1, and they are almost useless to highly mobile forces, except in the support role. Once located by an enemy they can be cut or tapped, with false traffic and re-routing of calls a real potential problem.

The internet itself was created to solve these issues, being designed as a 'web' like network rather than a linear or hierarchical structure, so that data can be rerouted around breaks in the system, so it always gets through to its destination.

For the live wargamer, despite being cumbersome and time consuming to set up and potentially expensive to buy, they are very easy to use., often requiring little or no training whatsoever on the part of the user, well almost...

14. Radio

|

This is the use of licence free Public Mobile Radio (PMR) or Citizens' Band (CB) equipment, for voice only traffic over short to medium ranges, or licenced Radio Amateurs operating global voice and data services.

Although comparatively expensive and insecure, it is in practice an extremely convenient and versatile means of sending complex, uncoded plain speech messages, without the users needing to be in sight of one another. Unlike a mobile phone, once purchased the radio costs little or nothing to run, and permits group conferencing as standard.

However, because most people are used to talking to one another on their mobile phones, many make the mistake of treating radios in the same way. Phones send and receive at the same time, PMR and CB radios do not. It is easy to cut off the front end of your sentence by the incorrect use of the Press To Talk (PTT) button, and to miss an incoming message by transmitting your signal over it. Training and practise are essential to good radio communications. See the series of radio articles starting with

The RTO's Page.

The use of PMR and CB radio is strictly controlled by legislation, and all operators must comply with all legal requirements. The sending of video images, Morse Code or computer data on PMR or CB channels is illegal. If you wish to send this type of material you will either need to go to amateur radio frequencies, for which you will need to acquire a Amateur Radio Licence, or more simply, if the era you are portraying allows it, a mobile phone, presuming you can get a signal.

|

⚠ WARNING ⚠ Note that microwave frequency communication systems are not considered safe for use in these sorts of activities.

|

Left: The ICOM IC-F29DR dPMR446 squad level transceiver. Click the image to go to the RTO's page to learn more about radio in

CONTACT.

|

|---|

15. Mobile Phones & WiFi

|

These are the easiest of the high tech mobile communication systems to use, simply because these days they form such a regular part of daily life. Models like the old Apple iPhone 5, pictured at right, can transmit speech, video and data streams as text or email messages. Phones, tablets, or computers can be interfaced to each other or to the internet. As long as the event is conducted within the range of the network, in effect the phone or other device's own range is unlimited. Also, unless you are a government, it is imposible to intercept or block your enemies systems. The downside is that not only is the kit not cheap, making players nervous about deploying it in the field, every second that your system is connected it is costing you money, and group conferencing is extra.

The other major problem remains getting a signal, without this, even the best equipment is useless.

In general these systems are best suited to either specialised or strategic level communications within a game, or when an event is conducted either from home or from safe and secure fixed assetslike the bunker as used for

CONTACT where there is little risk of loss or damage. Until the price of the tech and the calls falls, it will continue to mean that for now the radio still has a place on the modern wargamer's battlefield.

|

|

|---|

16. Cryptography

Finally, an article on communications would not be complete without a word or two about codes and cyphers, which is also spelt "ciphers", being the art of cryptography or "secret writing".

The first question that most people ask is what exactly is the difference between a code and a cypher?

-

A code is the replacement of a letter, word or phrase with an entirely unrelated representation. For example; the use of a codeword as an operational name, or for an agent's secret identity. Alternatively the use of tones of sound, flashes of light, or waves of a flag to represent a letter, word or phrase. There is no direct relationship between the two.

-

A cypher on the other hand is the replacement of a letter, word or phrase with another letter, word or phrase using a set procedure, that is an algorithm.

This algorithm renders the content unintelligible, a process called encryption. To decrypt the "cyphertext" back in to "plaintext", the recipiant must use the algorithm in reverse. Here the two elements are clearly related to one another, which means that an eavesdropper has a chance of working out what the plaintext actually is.

Codenames or their equivalent nicknames have been around ever since the first people wished to talk behind the back of another person, however cyphers had to await the developement of writing. This began with the Sumerians who developed Cuneiform, and the Egyptians who created Hieroglyphics, both around 5,000 years ago. The first alphabet appears with the Phoenicians 3,600 years ago, but it is not for another thousand years that we get the first known actual cypher called Atbash, which is a simple substitution cypher developed for use with Hebrew script.

Broadly there are two types of cypher:

-

Substitution cyphers: wherein using an algorithm each element of the plaintext is replaced by another to create the cyphatext, for example "A" is replaced by "B", and "B" by "C". This is a shift cypher.

-

Transposition cyphers: wherein an algorithm is used to move the plaintext around the page to form the cyphertext. For example a phrase is writen out so that each word is located within a column, then the columns are rearanged to scramble the message. The text itself is unchanged, just its layout.

One of the most famous early cyphers is that used by the Roman general Julius Caesar. Known consequentially as a Caesar cypher, it uses the idea of rotation of two alphabets, one written on an inner ring and the other on the outer. Julius Caesar used a shift to the right of three characters, so that "A" became "D" and "B" became "E". The reader of his letters, orders and reports merely reversed the algorithm to decrypt it. The same technique was employed by both sides in the American Civil War (1861 ~ 1865), see the image below left.

With the development of the internet and newsgroups, a need arose for a method of concealing spoilers and answers to quizs. So the Caesar cypher was tweaked with a shift of 13 and called ROT-13, meaning "rotate 13". This was chosen as which ever way you apply the algorithm, it will decrypt cipher text, making it a reciprical cypher. Other versions appeared; ROT-5 for the numbers 0~9, ROT-18, wherein both the 26 letters and ten numbers were combined, and finally ROT-47 that uses the 94 ASCII characters from #33 to #126.

|

Left: a Union cypher disk from the American Civil War (1861 ~ 1865), used to encrypt letters for use with the Wig-Wag signal flag system (see above). The outer ring was rotated to the agreed position, and the message encrypted by noting the numbers associated with each letter. The numerals around the edges define the direction in which the flag is waved, one equals left, and eight equals right. Eight was used rather than two, as it was considered easier to read. Remember Wig-Wag is similar to, but not the same as, Morse Code.

During the 20th century electro-mechanical encoders made big inroads, machines such as the Enigma pictured below right. And post WWII computing became the principle theatre in which the modern cryptographer worked.

|

|

Right: Probably the most famous encryption machine in history, the Enigma. Here showing the rotors, lampboard, keyboard and plugboard, all designed to make its cypher virtually unbreakable. But then the German military had not counted on

Alan Turing and the team of Station X at

Bletchley Park.

|

|

|---|

The following simple cyphers are printed upon either side of a laminated card and issued for use in the field.

All these cyphers are ones in which either row can be used as the start point for encoding or decoding. The letter above or beneath can be either the plaintext or the cyphertext as required.

The first is the ROT-13cypher, followed by an English alphabet version of Atbash, and the third is one of my own, from my misspent childhood.

THE ROT-13 CYPHER

|

A

|

B

|

C

|

D

|

E

|

F

|

G

|

H

|

I

|

J

|

K

|

L

|

M

|

|

N

|

O

|

P

|

Q

|

R

|

S

|

T

|

U

|

V

|

W

|

X

|

Y

|

Z

|

THE ATBASH CYPHER

|

A

|

B

|

C

|

D

|

E

|

F

|

G

|

H

|

I

|

J

|

K

|

L

|

M

|

|

Z

|

Y

|

X

|

W

|

V

|

U

|

T

|

S

|

R

|

Q

|

P

|

O

|

N

|

THE WAYLAND CYPHER

|

A

|

C

|

E

|

G

|

I

|

K

|

M

|

O

|

Q

|

S

|

U

|

W

|

Y

|

|

B

|

D

|

F

|

H

|

J

|

L

|

N

|

P

|

R

|

T

|

V

|

X

|

Z

|

|